Index

1:45

0:50

2:00

3:25

3:00

3:45

1:50

Welcome to our Transatlantic Webinar. We welcome those of you tuning in from Europe, those in Latin America, here in the United States, and certainly beyond. My name is Samuel George. I’m the Global Markets and Digital Advisor for the Bertelsmann Foundation. I’ll be moderating this conversation today.

We welcome in our partners, CADAL, Chatham House, and of course, our sibling organization in Germany, the Bertelsmann Stiftung. The BTI project, it’s available online, BTI-Project.org. Get all the information from the results on Latin America that we’re discussing today.

I’d like to pass our microphone to Hauke Hartmann, who is a cornerstone of the BTI project. I should add a scholar who is passionate about Latin America and has followed the region from a professional and academic standpoint for a number of years now. Hauke, please.

BTI focus on international dialogue Network of 300 experts Introducing the panelists BTI 2020 results sobering

The BTI is in itself a truly international undertaking. We are proud and privileged to operate in a network of 300 country and regional experts from more than 120 countries (Figure 1). So whenever our 5000 pages of country reports come out, we just can be sure that they carry the voices, the assessments of country experts from the very countries.

What does the

BTI offer?

Our regional coordinator, Peter Thiery is responsible for 22 of these country reports. He also was one of the masterminds behind the conceptualization of the Transformation Index. I do thank you very much, dear Peter, for introducing us to the results of the BTI 2020 in just a short while.

(Cooperation partner)

We are truly blessed to have a brilliant Argentinian cooperation partner, CADAL, in Buenos Aires for so many years now. This is the fourth time that CADAL not only translated major parts of the BTI into Spanish, and in fact, this webinar coincides with the publication of the fourth Spanish edition.

(Chatham House)

I met Chris Sabatini first when he was Senior Director of Policy at the American Society and Council of the Americas. But today, of course, we are privileged to have you with us here as Senior Research Fellow for Latin America at Chatham House.

(UN Chile)

What is missing in this lineup, of course, is a genuine Latin American perspective. With Viviana Giacaman, you’re getting a multi sectoral perspective. You are getting one that is informed by civil society, work with Participa in Chile 2021 with your on the ground work with activists as a regional director for Freedom House in more than 15 countries. Today you’re shouldering the important task of coordinating manifold activities of the United Nations in Chile.

One quick word about the BTI 2020. The results are sobering. The past decade was marked by a significant erosion of participation, rights and rule of law, a very volatile economic development and a persistently high level of social inequality, widespread bad governance, as illustrated by rampant corruption and clientelism. Most of these very problematic developments on a global scale very much apply also to Latin America today. Back to you, Sam.

Framing the conversation A decade ago, great prospects ahead Latin America faces a backsliding

Thank you, Hauke. I want to apologize in advance for sharing an old saying, it has almost become a cliche. It was first posited about Brazil. That it is the “Country of the Future”. It was actually a decade ago now when Latin America appeared to be entering a new era full of tremendous opportunity and advancement.

class has emerged

As the BTI noted, the commodity supercycle meant the region’s governments were suddenly very well financed, elections though flawed, had improved markedly. Countries from Mexico to Argentina took important steps towards consolidating the democracies. Brazil saw tens of millions of families transition from poverty to a middle class. In Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, we saw strong growth, monetary and fiscal stability. There was the feeling that for Latin America, the future had arrived.

Now here we are 5, 10, maybe 15 years later.There’s been definitive improvements in health, safety and that growing middle class. Underscored in this year’s BTI reports, many in that new middle class face a dangerous prospect of backsliding, further complicated by the coronavirus crisis. I would like to bring in Dr. Thiery because his presentation is going to help us understand how we got to this point.

BTI developments Challenges for consensus building Polarization Approval of democracy “Religious dogmas” Prospects in Corona times

Sam, thank you very much. I will make three points. First, a brief overview on developments throughout the decade. Second, challenges for consensus building. Third, I draw an outlook in corona times.

Peter Thiery

Senior Research Fellow,

University; BTI Regional

Coordinator Latin

American and the

Caribbean

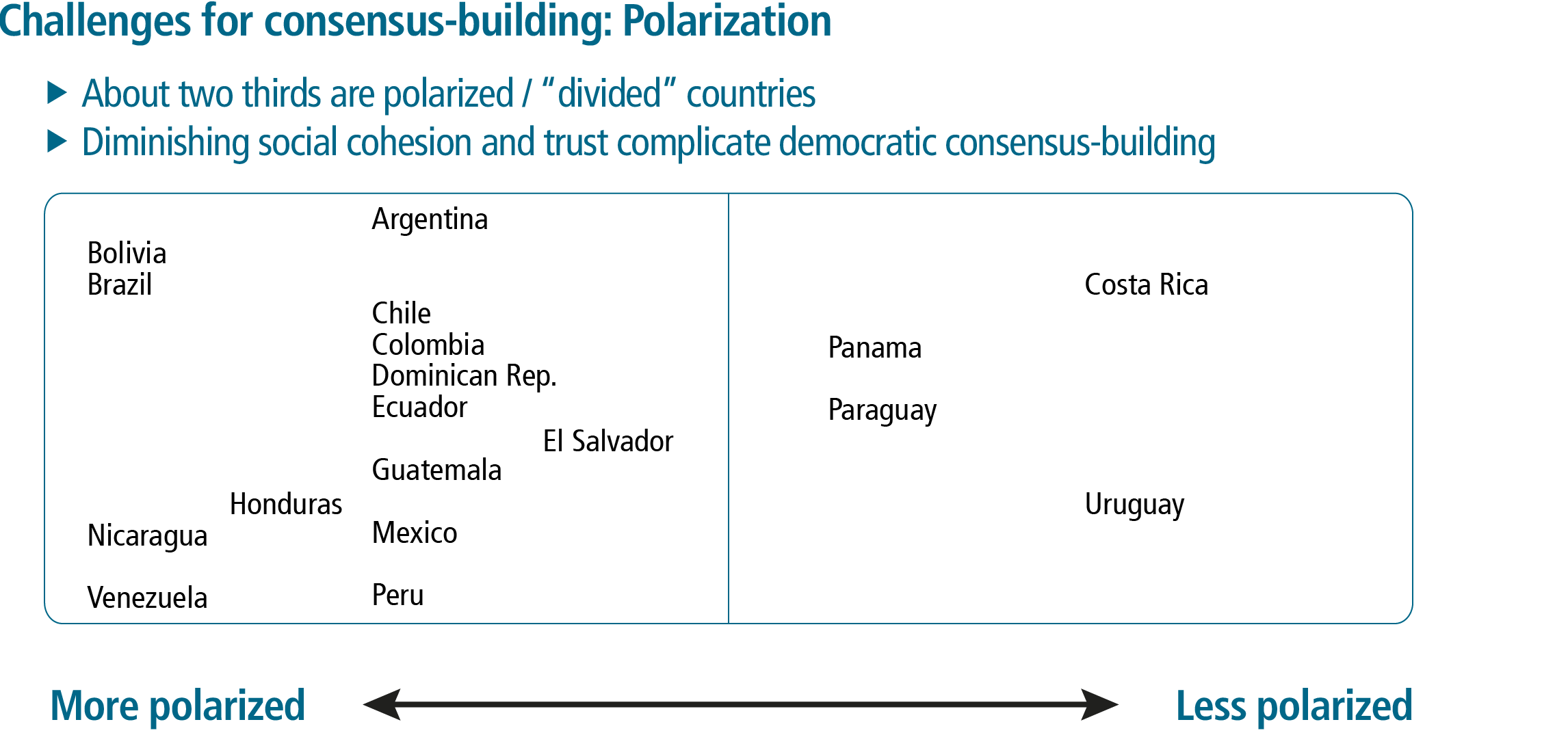

My overview on developments is on political transformation. We see first and this will not come as a surprise, that democracy in Latin America is stagnating, if not receding (Figure 2). Since 2010, we see a slight but a steady decline. How may we interpret this?

Political transformation

doubled; democracies

show certain resilience

The data shows that the number of autocracies has doubled from three to six in the decade after first Nicaragua, and then in the latest edition, Guatemala and Honduras were classified as autocracies. However, a look at the remaining 15 democracies (note) show that on average, there are no significant changes. That means there’s a certain resilience. However, the figure hides the fact that opposing developments balance each other. Various positive changes are offset by negative ones, particularly striking in the case of Mexico.

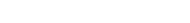

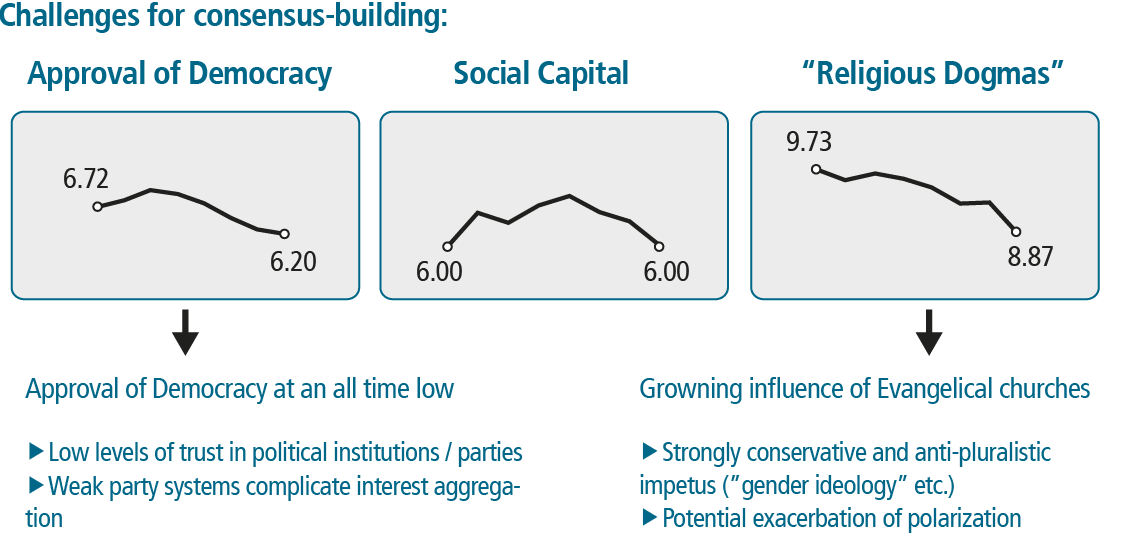

Second point: Challenges for consensus-building. I’ve chosen this issue because it points to a neuralgic point in the development of democracy. I made a rough picture of polarization in Latin America (Figure 3). It’s very simple that polarization implies that diminishing social cohesion and trust complicate democratic consensus building.

The approval of democracy is at an all time low (Figure 4). That means citizens confidence in the problem solving capacities of democratic institutions has declined, but authoritarian alternatives are gaining ground. This distrust also extends to individual political institutions, from the judiciary to parliaments and political parties. That means that the intermediation and aggregation of interest does not function sufficiently.

Approval of Democracy

and Religious Dogmas

The second point is religious dogmas. Our BTI indicator, named “No Interference of Religious Dogmas” is one that has suffered the greatest losses in the past decade (Figure 4). What does it mean? While the role of the Catholic Church is still very strong in some countries, the evangelical churches have gained more influence. According to the BTI Country Reports, this concerns almost all countries in Latin America. While some emphasize the positive role of these churches, I consider them to be a threat to state and democracy. This is due to the fact that these churches in general spread strongly religious conservative ideology. They have the potential to divide societies, as for example, in Brazil or in the recent presidential elections in Costa Rica. At the core, these positions seem to be intransigent and ultimately anti-pluralistic.

Third point: Prospects in and after Corona time. At present, the pandemic is still spreading rapidly. The pandemic lays bare or even exacerbates existing weaknesses. The concentration of power in the executive is sometimes abused, increasing debt burden, poverty and inequality, exclusion. However, this critical juncture might also present a window of opportunity for a paradigm shift. Perhaps we have now a new opportunity for solidarity, a big word, meaning the social cohesion can be constructed, but not invented from zero.

Peter, thank you very much for that presentation. It’s now my pleasure to transition to Mrs. Viviana Giacaman, who has had a front row seat to a number of the things that we’re talking about today.

The social contract has failed to benefit citizens The social contract has failed to create trust We have to recover better! On social cohesion

Thank you, Samuel. I want to make three points. First, the social contract has simply failed to provide the minimum wellbeing for the population. Second, we need to create a new one. The citizens must trust that the state will comply with their side of the bargain. As Peter just showed us, institutional trust is very low. Third, that new social contract should address the issue of social cohesion. Citizens must perceive that this deal is fair.

Viviana Giacaman

Strategic Planning Officer –

Team Leader, Resident

Coordinator Office,

So let’s go to the first idea that the deal has not benefited citizens. In fact, in the past years, Latin American countries have shown an increased incapacity to deliver on public services, education, housing, and health. They have not created social protections, have remained uncapable of dealing with organized crime or address corruption, have taken very timid or no steps to mitigate the climate crisis.

What happened? In the past 15 years, there have been an expansion of the middle class in the region, I would say from 25 to roughly 40%. That what we could consider a success story, actually made things worse! Because this new middle class has experienced such levels of vulnerability that it just stays fearing to fall back into poverty due to any event, including unemployment, illness, lack of income. The pandemic has proven those fears to be justified.

Poverty rates are projected to reach 34% of the population of Latin America this year. 28 million people will go back to poverty. Extreme poverty will be around 13%. Statistics say that only eight countries of the region have unemployment insurance for former workers.

Second point: The social contract has failed to create trust. According to the LatinoBarometro, only 14% of the population actually think that you can trust other people. In Northern European countries, it was about 60%, just to give you a comparison. The pandemic only reinforces those sentiments. The governments with low popular support before COVID shown greater difficulties to mobilize support around their health strategies. The official figures of people infected and dead are met with skepticism. This lack of trust provides the perfect environment for polarization and for the emergence of populist leaders that offer very easy solutions to problems that are complex.

We need to go beyond income and averages to understand the real magnitude of the problem. So let’s take gender inequality. The pay gap, for the best paying jobs in Latin America is about 30% between women and men. But there are other inequalities, right? So the fact that poverty among indigenous populations is 26% higher than non indigenous populations, that LGBTI communities have very limited health care services, the labor conditions of migrant populations are completely different than nationals. So there’s a long list… But the message is only one, an unfair deal is a deal that people will not abide by.

Third point: We need to look at the future now. Going back to business as usual will be a bad idea. We have to recover better, we’ll have to build back better. We have to rethink the way we organize our economies, the way we consume, the way we work, the way we produce. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel: The Sustainable Development Goals show a path for building a sustainable, inclusive fair development based on innovation with labor protections, rooted in a harmonious coexistence with the environment, to build a resilient society with more livable cities.

So let me conclude with a final note on social cohesion. As they grow, societies become more complex and diverse. But they can also become more fragmented. We are seeing this growing polarization, two-thirds of the countries, according to what Peter just told us. Social cohesion is that sense of community and solidarity, is a very intangible value that exists in society. Our interpersonal trust is not just a given characteristic of our society, or culturally driven. As Peter said, this values can also be developed. As we think about a new social contract, we should promote social relations based on respect of diversity, incorporating solidarity, social policy design, participatory decision making processes. Our current social contract is insufficient to address the demands of society, present and future.

also opens unique

opportunity

The wave of discontent we saw in the region last year was triggered by many different reasons, including the demands for political freedoms or even a 30 cent increase in the metro fare! But they were all manifestations of growing discontent. The pandemic has turned those existing problems into urgent needs. But also, it has opened a unique opportunity to step back, reconvene like we’re doing today, discuss and agree on a new path toward a more sustainable and inclusive development and a stronger democracy.

Thank you, Viviana, for that powerful and sobering presentation. Folks, I see we do have questions coming in. We’re just going to hold those for our Q & A Panel. But before we get to that part of the event, I want to bring in Mr. Chris Sabatini who has for a long time been a critical and really important voice on Latin America.

Batting cleanup We have measurement problems! Structural disintegration of societies Reasons for optimism

Christopher Sabatini

Senior Research Fellow

for Latin America, US and

the Americas Programme,

Chatham House; Member

of the CADAL Advisory

Council

Thank you, Sam. I have the honor and the challenge of batting cleanup. An honor but also a challenge because I want to echo a lot of the things you’ve said without sounding like I’m plagiarizing them. I met Hauke when the BTI was first starting. I at the time had developed the Social Inclusion Index. We tracked pretty much with BTI findings. So either we were both wrong or we were both right. I think it’s the latter.

I’m going to talk about three things here. The first is a little bit of a complaint or a gripe. It’s the problem of measurement that Hauke and I were talking about way back… The second is the structural disintegration of societies and state capacity in the ways that both Peter and Viviana have mentioned. Then the I’ll try to end on a more optimistic note. How do you re-stitch together the social fabric?

So let’s start with measurement problems. First thing that Hauke and I noticed years ago was the almost “intoxication”, if you will, over the rise of the middle class. Latin America alone, there supposedly 50 million people that joined the middle class. The problem is, when you scratch the surface, you found out that actually the way the World Bank was measuring the middle class was only income per capita of $10 a day. That’s it, didn’t matter how you got that $10 a day. You could have a formal job in a factory with benefits or you can be selling loose cigarettes on the streets at a stoplight. It didn’t matter. That was fundamentally wrong! This is a very dumbed down version of what constitutes the middle class. When we think middle class we assume that involves a stable floor of social benefits, health care, unemployment insurance. That is the middle class, it’s not just how much you earn a day.

The second point is structural disintegration of societies. More than 60% of Latin America’s working class population exists in the informal sector. Not only do they just work off the books, they also don’t have access to unemployment insurance. What we’re seeing now is a very bifurcated situation. People who have access to private health care, private education, or those who have access to very underfunded, inefficient public health care and public education.

be underestimated

shared identity”?

So let me shift to the last point, the reasons for optimism. Viviana’s suggestions are fundamental, providing social services in ways that are participatory, to build a sense of community and shared destiny, and not every person for their own. The truth is, we don’t have a roadmap for this, there is no precedent for how to rebuild a social contract. The closest thing I can think of was Robert Putnam’s Making Democracy Work, talking about Northern and Southern Italy. Social trust depends on people cooperating. We can begin to re-craft this I think post COVID. All the lessons we’re learning now are coming into a very sharp relief, that momentum needs to be maintained. Thank you.

Robert Putnam book? Evangelical churches? Pushing governments? Socioeconomic exclusion orchestrated ? Organizations to look at?

That name is “Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy”, released in 1993. One of the things he really talks about in that book about Northern Italy is the importance of civic society. Something as simple as choir groups, just having that kind of bond. An apolitical civic society really is one of the things that helped Northern Italy. Definitely recommended.

What do you see is behind this growth of the Evangelical Church in Latin America? What do you see is the long term impact of that? What’s driving that?

Good question. On the one hand, there is missionary appeal. On the other hand, there are spaces in Latin America where either the state or the Catholic Church lost the crowd. Around these structures, it’s not only a spiritual thing. It’s a welfare program. It’s a social network. It’s not a centralized church, it’s more decentralized. So they can easily adapt to any situation. That’s what makes them attractive.

I’m jumping in on that. European political parties post World War II, these were parties that were defined by one political scientist “cradle to grave”. They provided you benefits, they provided you a social forum. They provided you with your network and understanding and worldview. They no longer do that, evangelical movements do. They had soup kitchens for years that are feeding people. I thought, “Why weren’t the human rights groups doing this?” You need to build brand. I think in some ways, the evangelical groups have been far more effective at building grassroots presence than current political parties and many civil society groups.

As members of civil society organizations, how can we push governments to build back better, especially in a time of increased concentration and abuse of power, which undermine institutions?

What if the socioeconomic exclusion is not just happening, but is actually orchestrated?

It’s great that you’re with us, Hairo, another transformation thinker joining in with a very important question. Because as we are thinking about how to bring society back together, we should also bear in mind that this is an orchestrated and well-planned undertaking to drive societies apart.

Looking at the results of the BTI 2020, one of the headings that we are having is “unfree”, “unfair” on the political sphere and on the economic sphere. What if rules are well-defined, but are not necessarily well-played? There is a lot of protection of private property, a lot of competition policy, a lot of basics of market economic frameworks, but they do not play out to the detriment of those that are underprivileged. The political exclusion, the social exclusion, the economic exclusion, they are happening simultaneously. This is not happenstance. This is a power play. So any civil society move must be very aware that this is power politics.

I want to add to Hauke’s comment. Under colonial times, when the crown from Spain would pass all these rules and the saying was among the local’s imperial elite in Latin America, “I obey, but I don’t comply.” Yeah, well, sure, king! We just aren’t going to actually implement the law. That’s obviously still the case.

I worry that, for example, in Chile, the move to rewrite the constitution is a palliative. Yes, you need to rewrite election laws so that people are better represented in the famously closed system that is Chile. But you cannot pin too many hopes that will lead to effective implementation of those rights and rules in that constitution unless elites and the state are held accountable for what is contained in them.

Are there organizations that we can look to to help push for sustainable, fair, inclusive development?

It’s very, very interesting that these questions are about how to take action, right? If that’s the case, then I will feel very happy. Because this is actually the time to do that. As I said, in 2015, all countries signed the SDGs, that’s a roadmap, very detailed, comprehensive of how to have a better society. So what we need to do is hold the governments accountable, and help them be partners, and make sure that in the conversation, diverse views and perspectives are on the table.

Is there an optimistic note?

Thank you. As we near the end of our time, I’d like to just take one more trip around our panel, and invite everybody to suggest one concrete step forward, that you think would benefit the region. We always like to end on the optimistic note, what is something that people in Latin America and around the world can work on right now that could help get in the right direction?

First is to handle the corona crisis. We know that in North and South America it’s still growing. What happens if the pandemic is more aggravated? Will Latin America turn to authoritarianism? We have to wait. Second, it’s different from country to country. In Chile, you have already initiated the constitutional process. So the situation in Chile is rather different than the situation in Venezuela. You have to pose very different questions. In the case of Chile, I would recommend that civil society actors join and also join with the parties willing to reform.

Thank you, all. You guys out there, you’ve been an excellent audience. I want to apologize to some folks, we couldn’t get to your question. But we’re all available after this, email us, reach out, the BTI is online and highly recommended. We wish you a happy afternoon or evening.