Index

2:45

1:40

1:50

1:50

2:25

2:00

1:35

1:40

Welcome. My name is Brandon Bohrn, Manager Transatlantic Relations at the Bertelsmann Foundation. Today, we’re to be joined by four experts in their respective fields. It’s been a pleasure organizing this event with Miriam Kosmehl, Senior Expert for Eastern Europe and the European Neighborhood with the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe’s Future Program. We’re very thankful to be joined by Laurent Ruseckas at IHS Markit. Calling in from the Ukraine, we’re happy to have Mykhailo Gonchar, President of the Center for Global Studies Strategy. And finally, we’re thankful to have Sonja Peterson, Expert for European Climate and Energy Policy with the Institut für Weltwirtschaft.

Brandon Bohrn

Manager, Transatlantic Relations, Bertelsmann Foundation

energy crisis

How Europe will emerge from the current energy crisis will bear on how the world addresses the climate crisis. The soaring price of electricity challenges European leaders. They have either moved to halt the use of fossil fuels, natural gas included, at a quicker or slower pace. While natural gas is less polluting than coal, it’s still a fossil fuel producing emissions.

sparked a reckoning

over gas

Without a gas exit plan Europe will not be able to meet its own climate target, to reduce its emissions by 55% by 2030. Europe’s reliance on natural gas is at the heart of the current surge in electricity prices, because under European energy rules the price of gas drives the price of electricity. Gas accounts for a fifth of Europe’s energy consumption, and most of it comes from Russia. But while building out renewables infrastructure, countries in the Union continue to lean on gas. The energy crisis has sparked a reckoning over gas and undermined unity over how best to transition to renewables.

have surfaced

Divergences of interest have surfaced, especially on the issue of the gas pipeline Nord Steam 2, burgeoning U.S. LNG exports to Europe, and over the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism or CBAM. The EU wants to strengthen carbon pricing, but faces competitiveness problems for its industries if other countries do not follow. Amid the disarray, is there room for cooperation among transatlantic partners to overcome the current energy crisis?

Germany: Government formation and the energy issue Recent challenges mounting Gas exit paths to be defined EU neighbors are key allies

In Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe’s Future Program, we just started a project on the strategic management of global interdependence, which we see as a prerequisite for a sovereign Europe. For strategic capacity to act, dependency must be reduced where it leads to vulnerability. Strategic sovereignty in energy depends on three matters, sufficient, reliable supplies at economic prices not conflicting with a country’s values or interest.

Germany has traditionally focused on the market limiting the issue of energy to economic aspects. Other EU member states have been guided more by national sovereignty. Spain and Italy are currently pushing for a centralized platform for buying natural gas, similar to how the EU member states banded together to negotiate the price of coronavirus vaccines.

With these reflections in mind I turn to the three political parties that are to form the new German government. The non-binding paper launching the coalition negotiations emphasizes common ground in climate policy, but in rather general terms. Higher energy prices will create tensions among the Greens who push for a swift exit from coal and the Social Democrats who ran on a strong social justice platform.

How to finance measures must yet be agreed. And finally the three political parties view external energy policy quite differently. When Washington and Berlin this summer agreed on the further course for Nord Stream 2, the Liberals spoke of using a sticking plaster for a broken leg.

The Greens judged the settlement sent wrong signals to Moscow. The party’s co-chair, Annalena Baerbock, wanted to deny the pipeline its operating permit altogether. Less obvious is common ground with the Social Democrats. In their party program they do call for a sovereign Europe, a new European Neighborhood Policy, but they are distinctly more reticent in their responses to Russian leverage. So all eyes are now on which compromises will be made. I give three examples why this will be challenging.

When President Putin voiced that a quick approval of Nord Stream 2 would ease the gas shortage a hundred percent, the U.S. promptly recalled the Joint July Statement in which Germany and the U.S. threatened Russia with sanctions. My second point is while Gazprom is honoring long term contracts with the EU, it has been argued whether it should respond to higher post-COVID demand by filling its gas storages in the EU. In the EU Neighborhood, Gazprom has recently slashed supplies regarding Moldova, which is my third point. Russia urged Moldova’s new pro EU government to dilute its Free Trade Agreement with the EU and delay implementation of EU energy market liberalization in return for more supplies.

I end with two theses. Dependency on energy suppliers must be managed to reduce vulnerability. Energy policy and green transition are obviously two sides of the same coin. To obtain gas reliably in the transformation phase, the EU should define exit paths with its major suppliers. This however demands a smart Russia Policy and ideally U.S. cooperation.

Second thesis: EU neighbors are key allies. Reliable cooperation increases the EU’s scope for action. At the same time, they are especially vulnerable as the Moldova case has just shown. For sustainable European integration it is useful to include the neighbors as partners in the European Green Deal from the outset, rather than follow a “your taxed, now deal with it” approach. Here I quote a Neighborhood official at COP26…

Right out of the gate I’d like to turn to Laurent and just get your reaction to what you’ve heard thus far from Miriam and myself, especially as an American expert on this topic based in Europe.

The U.S. perspective: Nord Stream 2 and secondary sanctions US support for Ukraine key driver Relationship to Germany: Biden’s reset

Miriam, just on the point you raised. President Putin had said that they will refill storage facilities in the EU, which had not been filled over the course of spring/summer as they normally would be. So we’ll see. But in theory they did live up to what President Putin said, which of course is not much…

What the market would love to see is Gazprom to auction gas outside the context of its long term contracts, which it has not done. From the U.S. perspective, the driving force for the sanctions that have for some time stopped Nord Stream 2 were stopped because of U.S. sanctions passed at the end of 2019 being added into a big omnibus spending bill. And in Congress you hear a lot of the rhetoric that, “Well, this is bad for the U.S. because it will make Europe more dependent on Russian gas,” which is not. Europe has a certain amount of dependence on Russian gas for sure. And that’s true with or without Nord Stream 2.

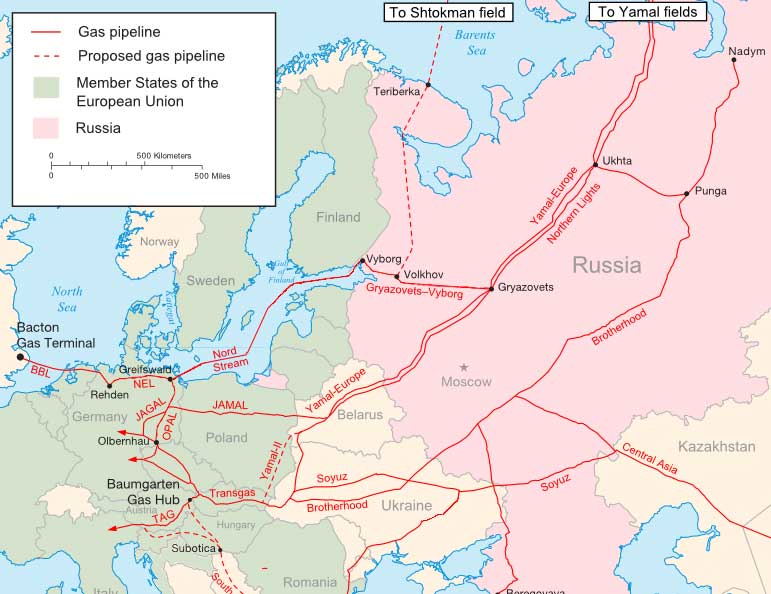

Major Russian gas pipelines to Europe

The driver actually in the U.S. has been support for Ukraine, an important ally that of course has had its territory occupied by Russia. That was the driver both in the Trump and then in the Biden administration. The sanctions from Congress are an example of secondary sanctions. All U.S. dollar transactions anywhere in the world have to clear through the U.S. This is an incredibly powerful tool that the U.S. typically does not use, but can use.

Even in the Trump administration there was nervousness. And then in the Biden administration decision’s made, we’re trying to reset our relationship with Germany. Climate is very important and Germany is a key partner. And so the decision was made to back off and that’s where the Joint Statement from this past summer came, but that’s not really about a view on Nord Stream 2. That’s a view on, we shouldn’t take a step that is in fact formally illegal in the EU, secondary sanctions, and use that to dictate policy.

I turn to Mykhailo representing Europe’s Eastern Neighborhood so to say. What’s your take on what you’ve heard thus far, Laurent’s comments, my comments, Miriam’s scene setter, especially from an Ukrainian perspective?

Gas delivery is weaponized A historical summary on Russia’s doctrines The “escalate to deescalate” policy Goal: Undermining the Green Deal

Thank you, Brandon. Yes, we have, frankly speaking, a very difficult situation! Gazprom, a state-owned company managed by Kremlin, has weaponized gas delivering to the EU and transit through Ukraine.

First of all, absence of pumping natural gas into Gazprom-owned storages in Europe. Next point, minimization of transit gas flows through Ukraine and our Gas Transmission System. Consequently, it means that Gazprom provided some manipulations. Next point. The transit through the Yamal-Europe pipeline was minimized and interrupted last week.

The actual situation is the result of Moscow long term policy that originates from USSR time. It was submitted to the Central Committee of the Communist Party in December, 1969. “An agreement on the supply of Soviet natural gas to West Germany may be of great importance. We are talking about concluding a contract that would be valid for two decades and would make such an important sphere of the German national economy to a certain extent dependent on the Soviet Union.” Let me now quote from the official energy strategy document of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2020, adopted in 2003. “Russia has significant reserves of energy sources, which is a tool for domestic and foreign policy. The country’s role in the world energy markets largely determines its geopolitical influence.”

Events that take place in the gas market of Europe should be assessed not so much in the system of market coordinates, but in the system of military strategy and hybrid special operations. That Russian doctrine “escalate to deescalate” is now being displayed at the gas theater. The escalation took place driving spot prices up to 2,000 dollars per 1,000 cubic meters, 40 times more than one year ago. Then suddenly Russia started to care about Europe. Bloomberg claims that Russia wants the gas price 60% lower to keep an energy grip on Europe. What is the main goal of this deescalation? It will contribute to further increase the share of Russian supplies to EU markets.

My last point. The goal is to undermine the Green Deal to preserve the European market for Russian fuels. The why is so important for the Putin regime! Russia is actually moving its gas, oil, and coal production to the Arctic region. This means the prospect of EU restrictions on environmentally harmful investment by Russia in the fragile Arctic.

Now turning to Sonja. I’d like to get your reaction to Miriam’s scene setter on the German case specifically. What do you think?

Carbon pricing has multiple merits Competitiveness effects, carbon leakage CBAM as a tool? Our advice: Agree on comparable action

I was invited to add another perspective to this discussion, which is noncooperation or cooperation not on energy markets, but on climate policies. And we’ve heard a lot already on the problems of noncooperation. That makes one forget that we have equally important issues on climate policy cooperation.

We’ve heard that Europe is taking climate policy very seriously. It has agreed on the European Green Deal, not only wanting to reduce emissions by 55% until 2030, but to become climate neutral at the mid of the century. That’s really a large task. And Europe is very strongly building its policy on carbon pricing. As an economist, I support this very strongly. Carbon pricing can give incentives to reduce emissions in a cost effective way. It avoids detailed interference of governments with the market system. It avoids making technological choices which might not be optimal in the end.

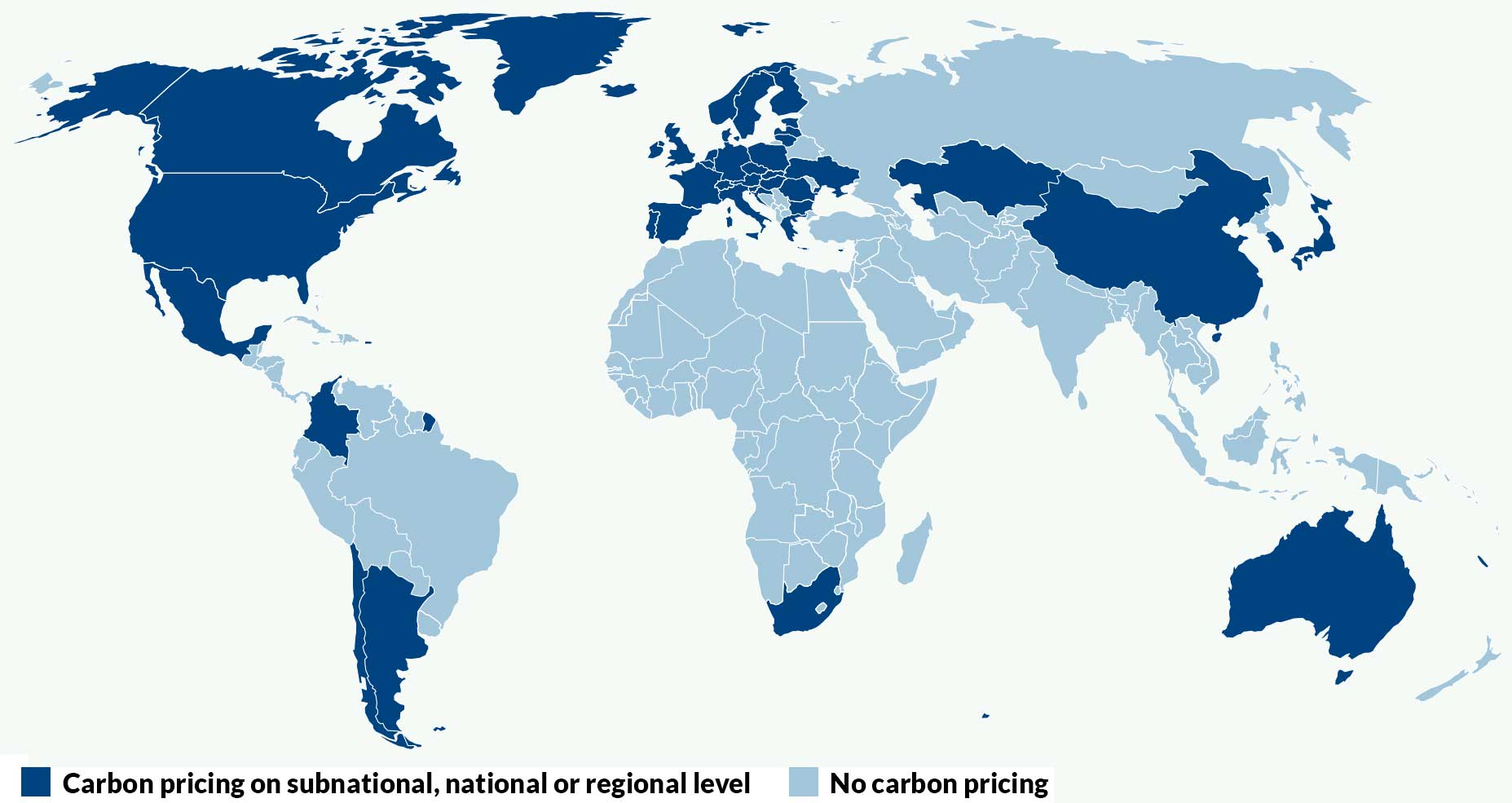

Countries’ Carbon Pricing,

World Bank, 2021

If Europe got carbon pricing and other countries do not, this leads to competitiveness effects. A large problem. Firms that do not face carbon pricing make it harder for Europe to reach its ambitious climate targets. Europe has all interest to avoid that economic activities being relocated to other countries. Emissions are moving to other countries then. How can Europe avoid these carbon leakage? As long as all countries don’t agree on an equal level of carbon pricing, the idea is to price carbon at the border.

And that is called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism or this nice abbreviation CBAM. Partners or other countries don’t like it. China has already stressed that it doesn’t support this mechanism. And it’s also actually a critical point between the U.S. and Europe.What we see so far, the approach is not to go for carbon pricing, but to mainly go through different types of government support and subsidies. And this makes this problem of carbon leakage even more difficult. Because you can argue, that makes it rather cheaper for the U.S. firms to produce and not in a way that prices carbon. So this makes it difficult to call this a cooperation.

That’s something our institution is pushing for very strongly, the idea rather than punishing countries in the first place, especially punishing the U.S., it would be better to agree on a joint level of effort in climate policy. And especially we would like to see a minimum price. Forming a coalition between the EU probably also Great Britain and the U.S., and then maybe later China, to agree on comparable action, to avoid CBAM mechanisms.

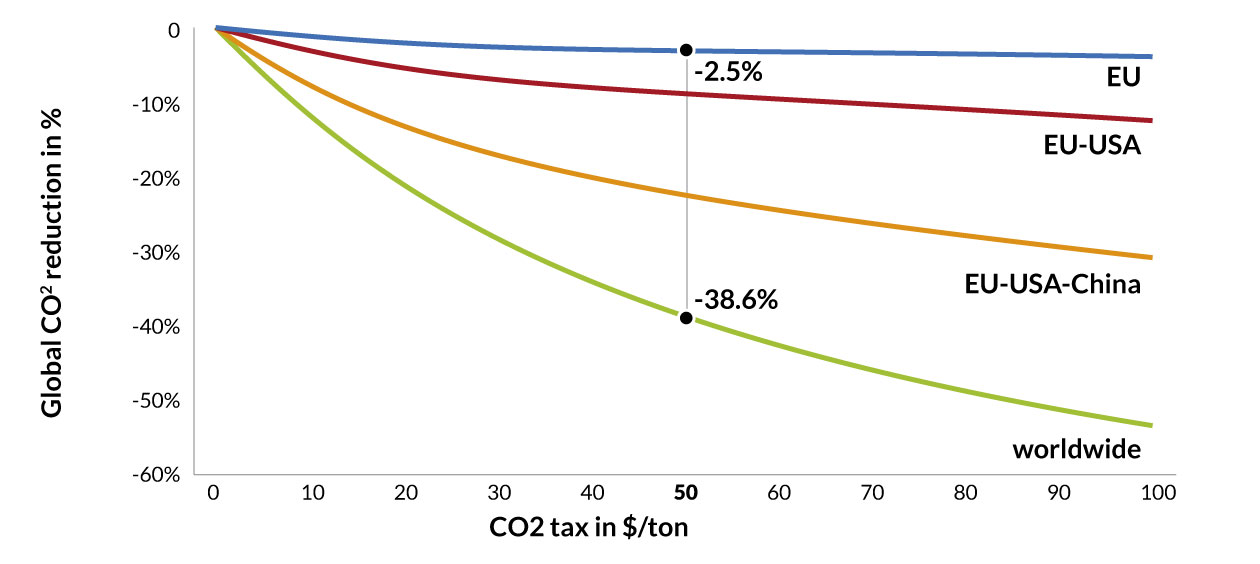

Comparison of emission effects between different climate clubs and the EU acting alone, Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2021

How to treat the Neighborhood? CBAM compared to value added tax Why not negotiate first, implement later? Give Russia different options for the future

I have a question to Sonja. The way I understand it, the EU will need cooperation particularly in the Neighborhood, because it will not be energy sufficient in the near future.

However, in the associated countries, you do have huge potential for hydrogen, for wind energy. So now my question is, if we look on the one hand at the economic integration the EU wants to achieve with the Neighborhood and the key role the neighbors could play in technologies and energy production, where does CBAM come in? What would be your advice as an economist?

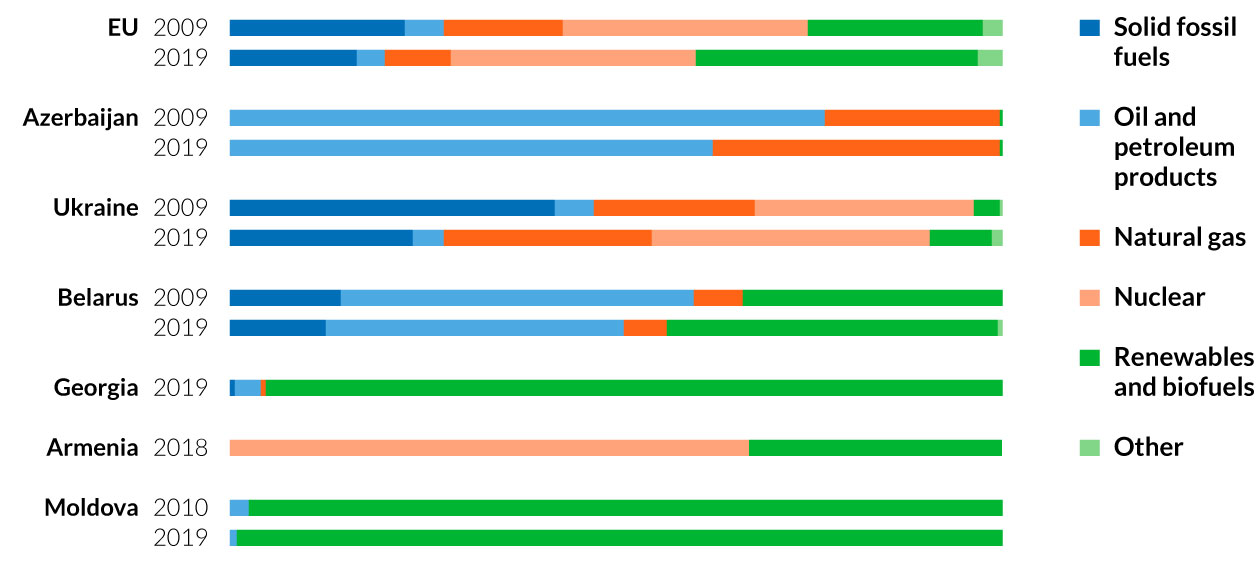

EU, Eastern Partnership primary energy production, by product, 2009 and 2019, Eurostat

What you were talking about is a lot that we need the near neighbors to produce our, hopefully, carbon free energy in the future even though I think there it’s also not clear how much the hydrogen economy will change the picture, but CBAM is addressing a different issue. Europe, especially Germany, is a large exporter of industry goods and these compete with imports from all over the world. The idea is that you need a mechanism to shield European industry from this competition. So that’s a different issue to where to produce our energy.

And that’s about making sure that if we implement in Europe the mechanisms to reduce emissions that does not lead that our industries are relocated to other countries. So that our industry basically loses. And I think that’s a fair thing. CBAM has often been regarded as a punishment to others, but actually it’s the same way as we treat value added tax. So when countries have different value added taxes, there’s an adjustment mechanism at the border. So it’s not that you treat imports from other countries differently than you treat your own production here. So it’s not that imported goods have to pay, I mean, worse than producers in Europe.

What the EU is planning is that it will treat imports into its territory the same way it treats firms that produce there. That can be justified. Still of course, it puts negative effects to importers, and it is an instrument where one could negotiate first and then implement it. And I think the EU maybe lost some opportunity there to first take this as a negotiation instrument before actually starting to implement it. What I see in the moment is that all these plans have advanced so much that the EU will not back up again. They have basically started the first steps on the European legislation level and I think it will come. You can negotiate with partners to not implement this if there’s comparable efforts in other countries.

I really think that there’s also large changes for cooperation. Russia has a large potential for renewable energy and maybe also for using them to produce hydrogen. It’s clear that Russia is dependent on selling its fossil fuels and that it can only lose from climate policy if it means that it has no export goods anymore. So jointly finding other export sources will be good.

2021 LNG market with two big surprises Now, Russia has leverage Gazprom fulfilling its contracts Methane leakage problems crucial

I’d like to turn back to a transatlantic focus. Congress and presidential administrations had labeled Nord Stream 2 specifically a dangerous geopolitical tool. But Germany quickly pointed to the U.S.’s own interests in expanding LNG exports to Europe. What’s your take on the matter?

I’ve heard that said a lot but I don’t really buy it. The driving force for U.S. negative attitude toward Nord Stream 2 has been supporting Ukraine. There’s not much overlap with U.S. LNG interest. By the way, one thing that’s different about state-owned companies and the U.S. system is that the president and the government have no influence on where U.S. LNG goes. Gas is free to go to the market that will pay the most. And that’s in Asia.

Mykhailo spoke about gas being used by Russia as a weapon, and I think there’s a reason why you haven’t heard that rhetoric from most European countries, and certainly you haven’t heard that at all in the gas industry because there’s a bigger picture here.

The start of the story has to do with precisely the LNG market, where we had an upside demand surprise this year on LNG and Asia recovering from COVID. Then you had a downside surprise in terms of LNG supply. There were six or seven liquefaction plants around the world which had shut downs.

And this is the only circumstance in which Russia has real leverage or market power in Europe. Normally, the LNG market sets the price in Europe and Russia has no power. But we had a circumstance where all of a sudden LNG markets were tight and Europe has created a gas market which works great until it doesn’t. Gazprom was put in a position to be supportive…

Gazprom has chosen not supplying more gas outside of its contracts. I think it’s very hard to make the claim that they’re weaponizing it by saying, “Well, we’re fulfilling all our contracts, and beyond that we’re holding back.” I don’t think that the weaponization really fits. I mean, Russia weaponizes other things, and it has done so in Ukraine.

So final point, methane is incredibly important, probably the most fundamental issue for the Russian gas industry over the next decade. The world is getting serious about methane. Everyone understood that this is one thing that we can do quickly and easily. It’s a big problem in the U.S., but Russia, and I think they know this at this point, it’s going to have to address the methane leakage problem. In the latter days it’s building newer infrastructure like Nord Stream 2, but the problems in Russia concerns the oldest parts of the system.

We need a “divorce process” for oil and gas Europe is as weak as it chooses to be Why not import renewables one way or the other? Is EU energy sovereignty a good target in itself?

Turning to Miriam or Sonja now. On the one hand we have the U.S., on the other we have Russia with their own interest. Europe is in the middle here. What do you think about Europe’s role in achieving sovereignty?

The more unity we’d have in the European Union and ideally in good cooperation with the U.S., the stronger our position and the better the prospects.

In the case of Russia we are faced with the challenge of structuring the “divorce process” for oil and gas with as little conflict as possible and in a balance of interest. And that, of course, is a political challenge!

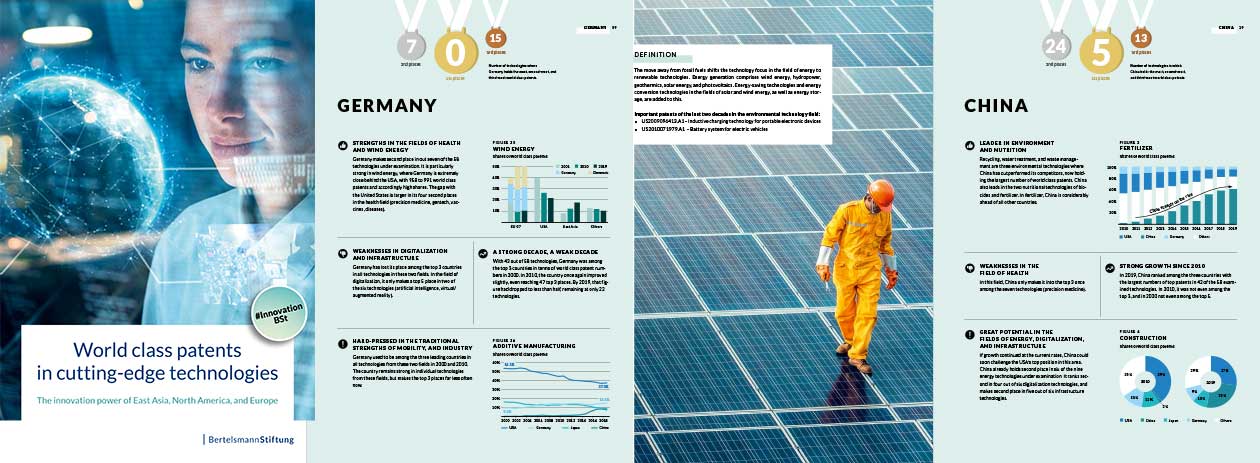

A recent Bertelsmann study on world class patents has shown how rapidly China has expanded its position in innovation-driven energy sectors, and that Germany has lost its once-top position in photovoltaics to China. This is what I mean by Europe is as weak as it chooses to be. It does have the potential to have a very strong role in these challenging fields. But this involves its ability to develop and invest in key technologies.

Maybe I have a different perspective. I’m not sure if it’s really the best goal for Europe to become energy independent or sovereign. There are good reasons to explore its cost differences and different comparative advantages.

In the moment Europe is importing fossil fuels. I’m not sure if not in an optimal setting in the future, Germany is importing renewable energies in one way or another. It doesn’t have to necessarily be a bad thing if you import renewables one way or another where they’re abundant, especially maybe in North Africa. We have this desert tech idea. Maybe it can be revived.

I don’t see that Europe is really on a way to increase its energy efficiency so strongly, and to really just rely on European renewable resources. To produce or to export renewable energy in Russia, but maybe also North Africa, the Middle East, might be a chance to get new countries on board in climate policy. So for me, the geopolitics are not so clear there. Becoming completely energy independent might not be a good target in itself.

Is there an optimistic note?

I’d like to just take one more trip around our panel. What gives you optimism looking into the future?

From my point of view, what do we need? We need transatlantic energy solidarity between the U.S. and the EU, energy solidarity inside EU. The Court of Justice of the EU accented energy solidarity as a main principle in accordance with the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU. It’s very important. And next, a track of solidarity between the EU and Eastern European countries, Ukraine and Moldova first of all. Gazprom is a dominant player and dependency of Europe exists, is a reality. We need more diversification.

The two most positive developments in terms of international climate policy are that the U.S. are back in the arena and that they clearly are moving into a good direction. That will make a large change because the U.S. is the second largest emitter. I also do see it positive that China has started its National Emission Trading System this year. China, being the largest emitter in the world, is moving also towards more stringent carbon pricing. I hope that this will help on a global level to achieve more ambitious targets.

The Nord Stream 2 debate has been very destructive in a lot of ways. At a certain point, the pipeline will start operating. It won’t have any negative impact except on Ukraine. We should see joint efforts to support Ukraine. We have a U.S. administration that wants to cooperate with Europe. I don’t think Russia using its gas weapon is going to change EU policy on the Green New Deal. So that’s where my optimism is, is what can be achieved in the next few years on U.S.-EU climate cooperation.

What gives me hope is the green transition generally. It gives the European Union the opportunity to establish Europe as a stable and sustainable continent. A key issue will be, as Mykhailo said, the extent to which states cooperate within the EU and beyond, and focus on global goods rather than on their own short term advantage. If this attitude would spread, I’d be confident.

Wonderful. First I’d like to thank the panel for taking the time to participate in today’s event. Having such a wealth of expertise on one panel is quite a privilege for us. Thank you very much to the audience for joining and please be on the lookout for more webinars related to the recent German Federal Election.